Why dropping a street from 4 lanes to 3 is better for everyone (even drivers!)

Road diets are one of the most useful tools in a traffic planner’s arsenal. They’re also one of the hardest things for drivers to wrap their heads around. If traffic is bad with four lanes, it has to be even worse with three lanes, right?

Wrong. It’ll be better for everyone, driver’s included. Let us explain:

An example of this dynamic is currently at play on 2100 South in Sugar House. Today, the road is striped with 4 car lanes plus on-street parking—there are no bike lanes and the sidewalks are unattractively and dangerously narrow. The roadway is typically clogged with bumper-to-bumper traffic and is actively hostile to people on bike, foot or bus. A motorcyclist was killed there in August, a pedestrian was left critically injured on Halloween.

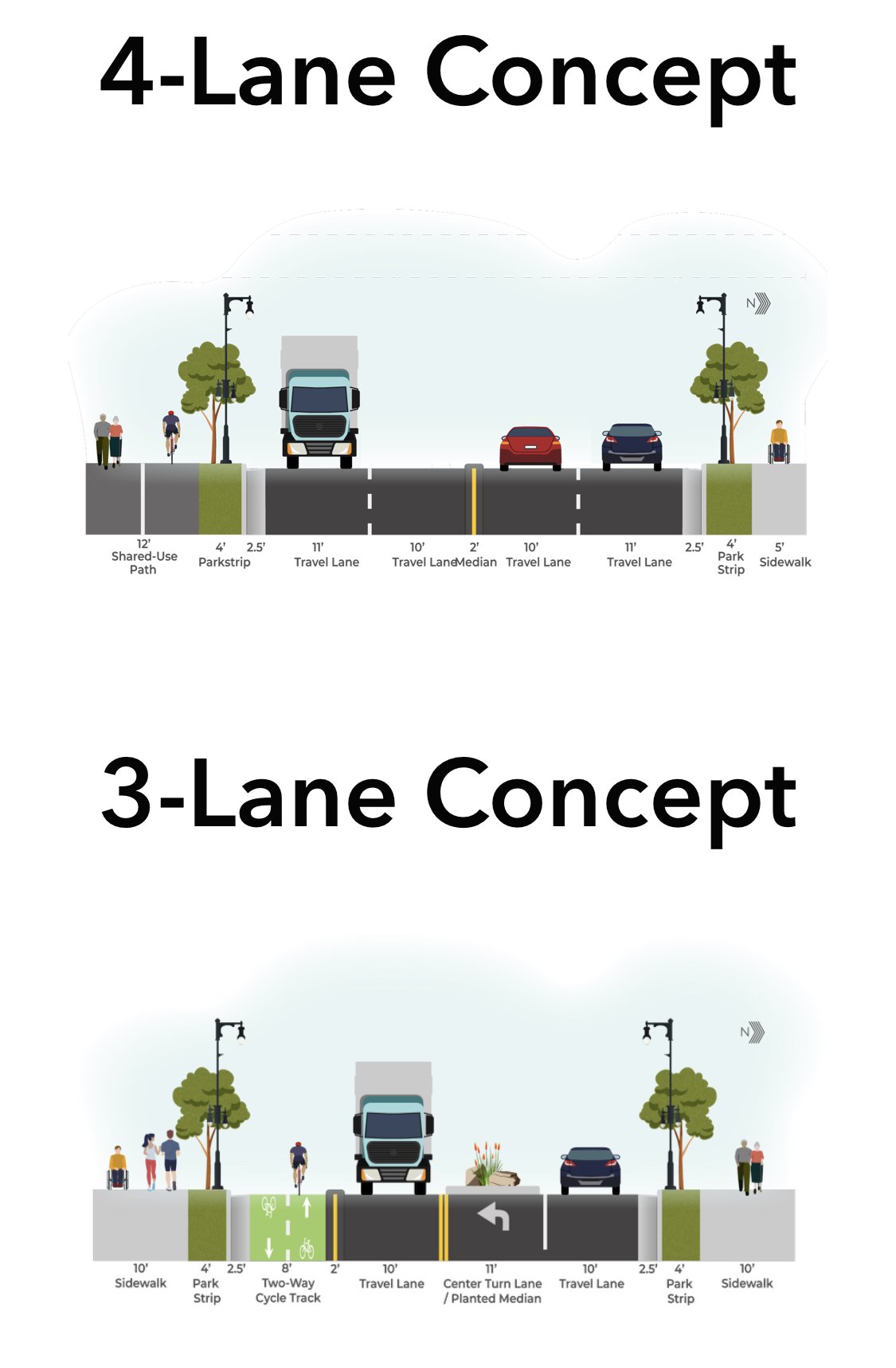

City planners are exploring two redesign options: a 4-lane street with minor safety and pedestrian improvements to the existing layout; or a transformational 3-lane configuration that would add bike lanes and a wide walking path, turning a busy surface highway into a de facto Main Street for the Sugar House neighborhood.

Now, picture yourself driving on a four-lane street, two lanes running in each direction. You’re in the right-most lane but somewhere up ahead, someone is trying to make a turn and a line of cars is starting to form behind them. So you switch into the left lane to get around the bunching, only to find that someone even further up ahead is trying to turn left, causing the same car crunch in that lane too.

Every time you zig-zag-zig to try and get through the cars around you, you disrupt and ensnarl the flow of traffic. Problem is, you’re not the only one doing this—every driver is feeling the same compulsion to weave their way, freeway style, through a city street, leading to a chaotic jumble of movement that makes blind spots blinder and motivates small bursts of unsafe speeding to try and “beat” other drivers through an intersection or around a turn. Add in parking, pedestrians, cyclists, buses and any number of spontaneous complicators and you have … well, the typical American stroad: an unsafe death trap that satisfies no one and angers everyone while claiming an unacceptable amount of human life every year in the name of “improved” commuting times that can’t actually be measured in the real world.

Road diets fix this by prescribing order to the chaos. Instead of parallel travel lanes that pull triple duty as passing and turning lanes, you have a single travel lane in each direction for anyone looking to move forward: period. A center turn lane moves the stationary vehicles out of the way and, when turning, a driver need only cross a single lane of oncoming traffic instead of shooting the gaps of twin lanes, meaning the queued cars clear out quicker and with more ease. An individual driver may experience something that feels like congestion—simply because they no longer have the option of a “passing” lane—but in reality it’s a momentary inconvenience that when zoomed out shows a much more free-flowing system for all parties involved.

Then there’s the benefit to everyone else not in a car (it’s true, they exist!). Three lanes is obviously easier for a pedestrian to cross than four—particularly since a car stopped at an intersection blocks the view of parallel drivers—and the reduction of car lanes opens up road space for a pair of bike lanes (effectively turning a 4-lane road into 5), for trees and landscaping, for pedestrian refuge and bus-loading islands or hell, even for more curbside parking at local shops and restaurants. And for the drivers who are trying to park, doing so against a single lane of traffic is considerably easier, and safer, than two.

In his book Walkable City Rules, Jeff Speck describes a study of 23 North American road diets, which found the average volume of car traffic increased after 4-to-3 lane conversions. Notably, this increase in traffic volume corresponded with a dramatic decrease in collisions and fatalities. If you want to drive faster while not killing people, 3-lane roads are for you, my friend.

“We now know that there is no reason for any urban street in America to have four lanes,” Speck writes. “It cannot be justified.”

The more holistic issue with 4-lane streets is that they train drivers to expect a highway—everywhere. But picture the traffic on a 4-lane street from the perspective of the other things on that street. Is a local business helped by the cars that pass through without stopping? Are the residents who live nearby? If you’re coming here to stop somewhere else, why are you here at all?

A road diet declares, definitively, that *this* is not a highway, it’s a street. It says “If you’re here, you should have a reason to be.” That can be hard to swallow for drivers who don’t like being told what to do, but one touch of their foot to the gas pedal and they’re off like a bolt of lightning to terrorize the next stretch of asphalt. (And lest we forget, we’re still giving them 3 lanes to drive on as they please.) The real insidious aspect is that many of the pedestrians, cyclists, transit riders—even DRIVERS!—who would like to stop on that street and spend some money will choose not to, pushed aside to other, more comfortable places by the very car traffic we’ve chosen to prioritize.

Unfortunately, people aren’t always great at recognizing what’s good for them. And unfortunately, city transportation officials often lack the backbone to insist on doing the right thing. And mind you, when we say the “right thing,” we’re not talking about eating your vegetables, we’re talking about a delicious dessert that you have to try to understand—one where bustling foot traffic and window shoppers replace the roar of non-stop vehicle movement.

The most recent word from Salt Lake City planners is that 2100 South will use a “hybrid” approach, trying to cram together aspects of both the 3- and 4-lane designs—which likely means the result will be a confusing hodgepodge of compromises that achieves little and satisfies no one. Sugar House deserves a Main Street, and residents deserve a design that treats them with respect and dignity, and not just as obstacles for drivers to get around.

Are there any 4-lane streets by you? Contact your community council, city council representative and/or city transportation representatives and tell them it's high time for a diet.